I am not fascinated with my family tree as simply a collection of genes, but in how history and war and geography shaped that tree. Orangeburg, South Carolina is a huge part of that. Orangeburg was where the Beckwith family and the Moorer family came together. I kind of knew that, but hadn’t dug out the details of it because I’d assumed the story was boring and full of people named Henry growing corn.

Burnt out on researching the Martin family, I set out to answer the questions of why and how the Beckwith family came to Orangeburg. I wasn’t expecting much, but what I began to unearth was, to me at least, kind of amazing in its dramatic expression of our country’s violent relationship with itself.

Laurence Ranson Beckwith* was born in Columbia, South Carolina in 1842. Two short autumn months after L. R.’s eighteenth birthday, his home state would be the first to secede from the union. When he enlisted in the 6th Regiment South Carolina Cavalry in Columbia on June 12 of 1862, he brought with him a horse valued at $250 and equipment worth $60. Shortly after being furloughed with grave injuries two years later, he would carry with him the rank of of First Sergeant, the remains of a subordinate, and a bearing towards that man’s family burial ground in the rural countryside. America’s bloodiest war officially ended before Beckwith’s twenty-fourth birthday.

Laurence Ranson Beckwith* was born in Columbia, South Carolina in 1842. Two short autumn months after L. R.’s eighteenth birthday, his home state would be the first to secede from the union. When he enlisted in the 6th Regiment South Carolina Cavalry in Columbia on June 12 of 1862, he brought with him a horse valued at $250 and equipment worth $60. Shortly after being furloughed with grave injuries two years later, he would carry with him the rank of of First Sergeant, the remains of a subordinate, and a bearing towards that man’s family burial ground in the rural countryside. America’s bloodiest war officially ended before Beckwith’s twenty-fourth birthday.

[UPDATE: I recently discovered that L. R. Beckwith served alongside his younger brother in the Infantry prior to his service with the Calvary]

The son of Laurens Butler Beckwith and Harriett Hunt, L. R. was the type to show up later in books about prominent Virginia families, even after being born himself in South Carolina. L. R.’s grandfather had two middle names and a plantation, the son himself of an English baronet. They married people who were related to people who signed the Constitution when they weren’t marrying their own first cousins.

According to Some Prominent Virginia Families (Volume 4, Page 24), L. R. was captain in the “Hampton Legion,” Confederate States Army. However, I’ve had some issues with this particular book, so anything that I get from it is pretty much for “good starting point” value only.

The more I looked into the captain claims, the funnier they smelled. Finally, my nose led me to Battle of Trevilian Station: The Civil War’s Greatest and Bloodiest All Cavalry Battle (Col. Swank, USAF Ret.), a book that had both the story and some documentation to go with it. 1st Sergeant Beckwith’s military career ended in Louisa County, Virginia in June of 1864. The paperwork for his furlough was done by July. Advertisements for an insurance agency that L. R. was involved in during the 1880s list his name with no title along with an associate who is designated as “Capt.” I’m pretty confident that Beckwith was indeed a first sergeant when he was taken to the C.S.A. General Hospital in Charlottesville, Virginia with service-ending injuries at the age of twenty-one.

Laurence stayed in the C.S.A. hospital from June 13 to July 5. The details of the medical board examination are at the National Archives and this is my official note to myself to go look at those next time I’m in DC. Confederate Archives, Chapter 6, File 215, Page 362.

Col. Swank (RET) prints in his book a letter from Robert B. Wilkinson, Jr., of St. Matthews, that provides some detail to the story:

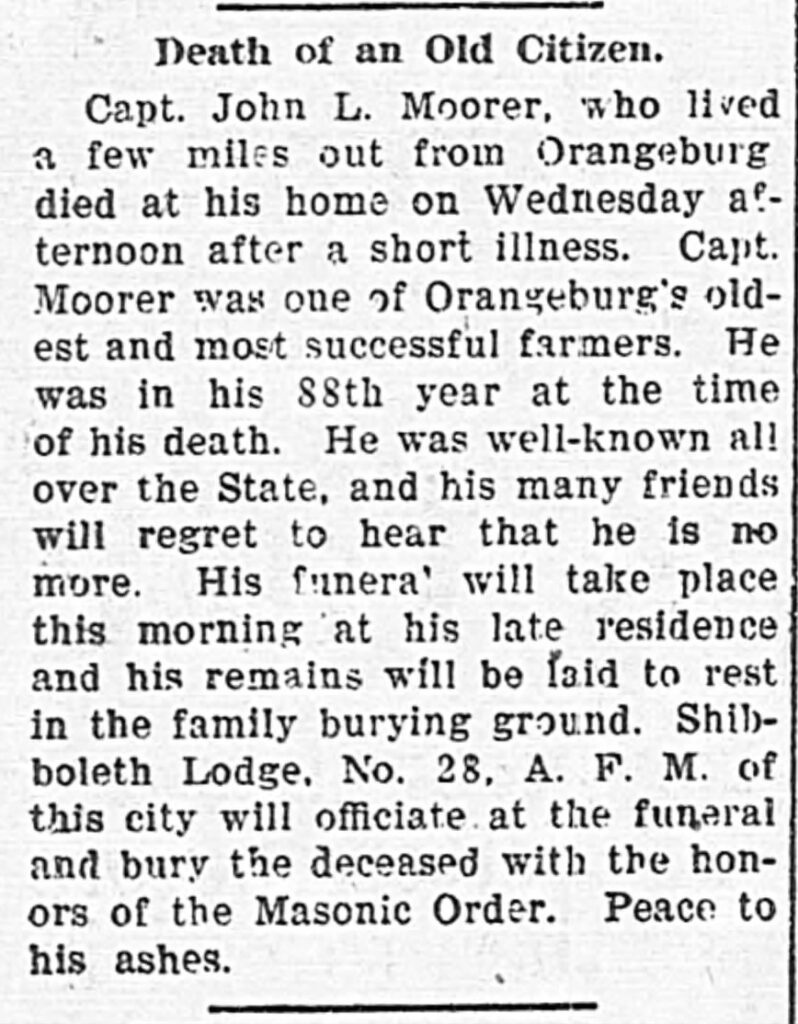

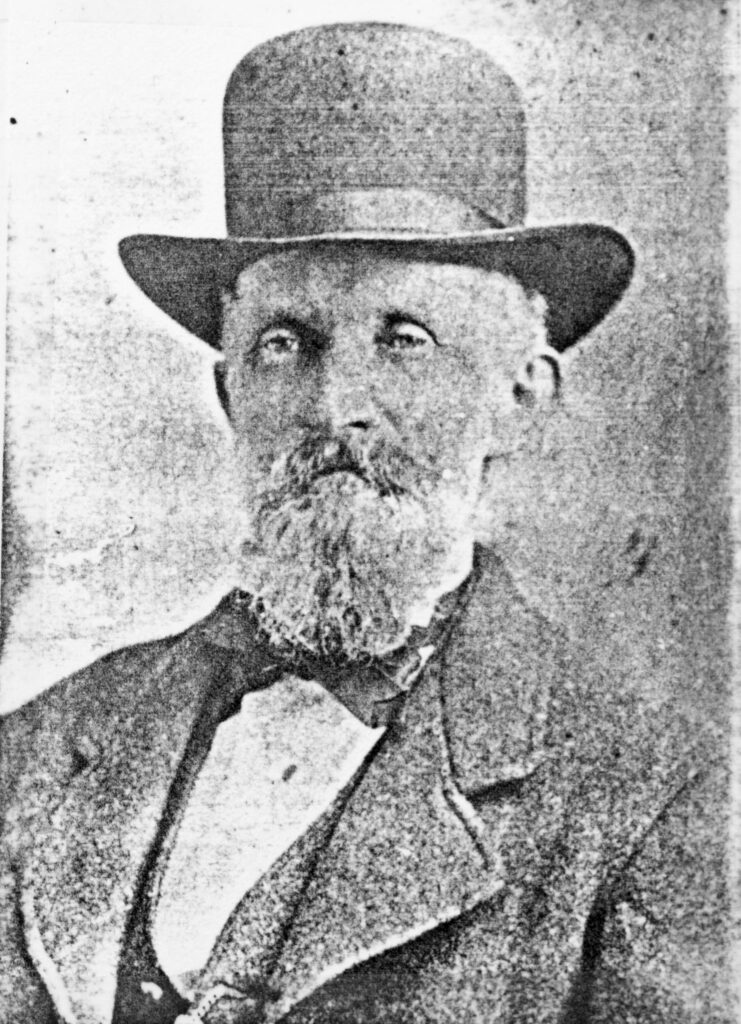

Francis Marion Moorer was the great-great-great uncle of Robert B. Wilkinson, Jr., and Captain John L. Wilkinson, USAF, of the Wade Hampton Camp #273 of Columbia, S.C. He was born Jan. 1, 1825, in Orangeburgh District, being named for the “Swamp Fox,” (Francis Marion, who was one of South Carolina’s heroes of the first war for independence) under whom his grandfather served in 1781 as a lieutenant. At the time of his enlistment on Dec. 21, 1861, “Frank” as he was known, was a moderately successful planter. His plantation ‘Magnolia Grove,’ was built in 1810 and inherited from his father. It was built adjacent to his great grandfather’s land (who was one of the first settlers of Orangeburg, S.C., in 1735, a Swiss.) He was enlisted at the age of 36, in the 20th Regiment, S.C. Volunteer Infantry, later Company B, under Capt. P.A. McMichael, serving on Sullivan’s Island and the defenses of Charleston, S.C. On Feb. 1, 1863, he requested transfer to the 5th S.C. Cavalry, Company A and served with them in Charleston until called to Virginia. While serving under General Wade Hampton’s command, he was mortally wounded in the fighting at Trevilian’s Station, Virginia, on June 11, 1864. He died the next morning. His young friend, Sgt. Lawrence Ransom Beckwith, marked his grave. (Beckwith was also wounded in that battle.) Beckwith who was to become Frank’s nephew after the war, returned to the grave with Frank’s brother, John Lewis Moorer and a two horse wagon. They recovered his remains in some sort of bag and solemnly rode the 460 miles back to their home. His final resting place was the old family burying ground on his great grandfather’s land. Frank’s widow and two daughters survived the barbaric horde of Gen. William T. Sherman eight months after his death only one daughter was to survive past 1880 on the impoverished plantation.

As Mr. Wilkinson alludes to, after his return to Orangeburg with Pvt. Moorer’s brother, L. R. stayed and married Ann Hess Moorer a short time later. L. R. went into business with the Moorer family, competed in the local agricultural fair against them, and was buried in the cemetery alongside the man he had once fought great and bloody battles with.

There’s so much more to the story, but in the interest of actually hitting Publish on this thing, I will save that for another time. L. R. died in 1884 at the age of 42 and the second half of life may be worth even more discussion than the first. Reconstruction was not an easy time for men like Beckwith.

*Laurence Ranson Beckwith’s first name can be read in his signature as either Lawrence or Laurence. I usually see it written by other people as Lawrence because that is the traditional spelling. His middle name is printed in some records as Ransom and others as Ranson.

I believe the first name is Laurence and middle name is Ranson because he named his son after himself and that son’s name is most definitely Laurence Ranson Beckwith (1898 – 1907). That is how the name is spelled on the son’s gravestone in the cemetery of Prospect Southern Methodist Church in Orangeburg, South Carolina. That gravestone would have been erected under the direction of the senior Laurence Ranson Beckwith himself and most certainly wouldn’t contain a misspelling.

It is also worth noting that, a generation before, the family lived in what later became Ranson, West Virginia. Either way, it seems that he went by L. R. Two Three of L. R.’s grandsons (including my grandfather) were named Laurens so the name thing is of a bit of interest to me.